21 Years for Paul Doyle, a Lifetime for the Victims

Why the parade attack can never be reduced to a moment of anger

Liverpool Title Parade Attack: Rage, Myth Making, and the Lives Left Behind

I’ve followed Liverpool long enough to know that the city keeps its receipts. Joy, grief, injustice, the lot. It remembers faces, it remembers streets, it remembers the sounds that hang in the air long after the flags are folded away.

So when a Premier League title parade in Liverpool, a day built for noise and colour, ends with a car driving into supporters, you do not file it away as an unfortunate footnote. You carry it. You carry the photographs, you carry the footage, you carry the uneasy truth that a celebration can be turned in seconds by one man’s temper and one man’s entitlement.

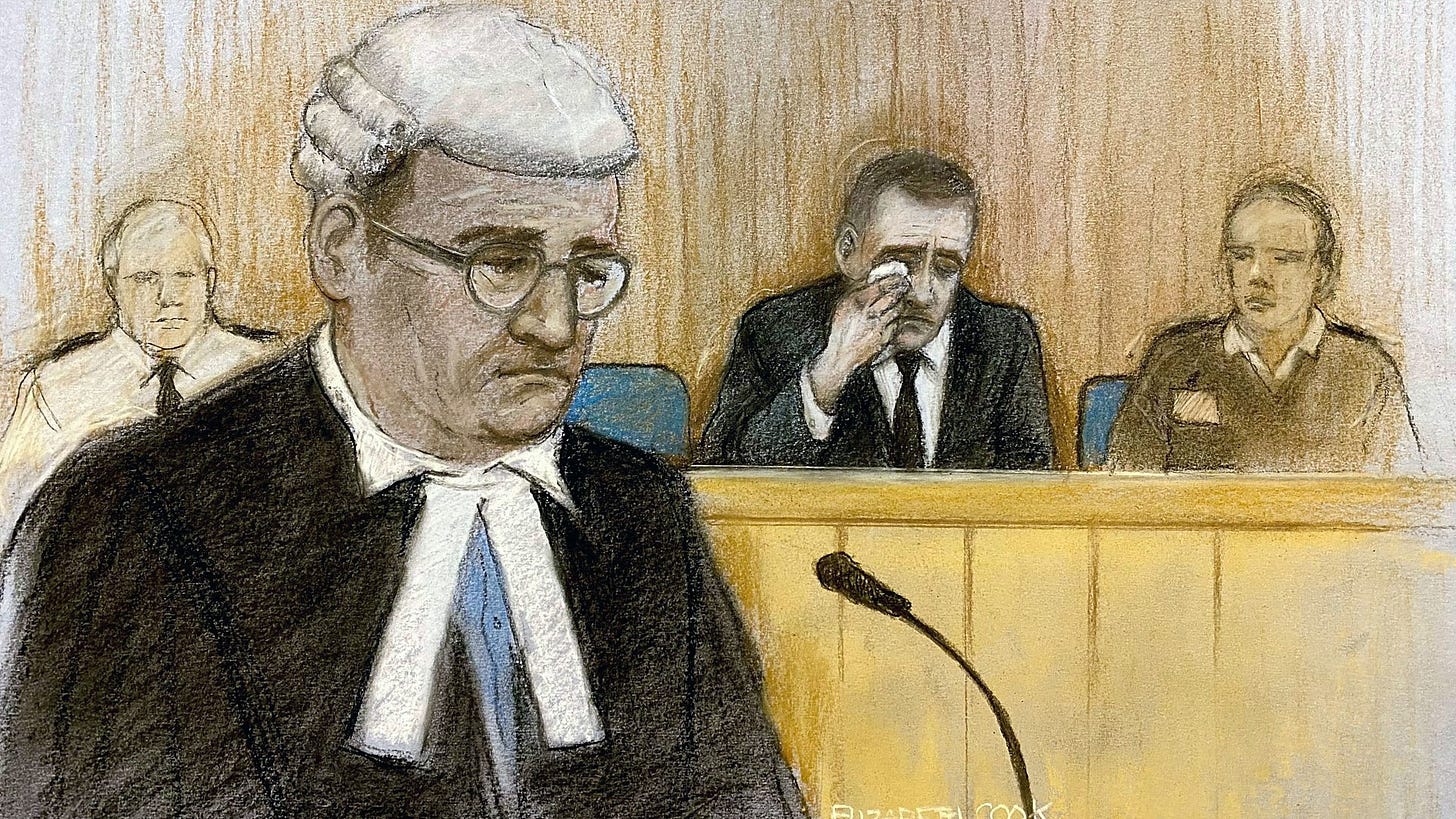

Paul Doyle has now been sentenced to 21 years and six months in prison for driving into Liverpool supporters during that parade. For anyone who watched the bodycam, the dashcam, the CCTV clips that made the rounds, this was never a muddle of panic. It was force applied to flesh, and it was done with intent.

And yet, for a while, there was an attempt to dress it up. To soften it. To make it easier to look at.

That is what I can’t shift.

When a car becomes a weapon

There are details from that day that do not need embellishment. They have their own weight. Supporters packed into streets that had been closed to traffic. Children among them. Prams. People who had turned up early, stood for hours, sang themselves hoarse, then began the slow shuffle home with that floaty feeling you only get after a proper communal day out in Liverpool.

Then a vehicle goes through them.

Not a brush, not a scrape, not the sort of stupid accident you see when someone clips a wing mirror in a tight lane. This was driving into a crowd, accelerating into human beings, using a car as a way of clearing a path. Some victims ended up trapped beneath the vehicle. Even when the car had stopped, there were reports the engine could still be heard revving, the pressure not fully lifted, the moment still trying to go forward.

If you want the clearest glimpse of Doyle, you can find it in what he reportedly said in the police van afterwards. He spoke about ruining his family’s life. On one level, that’s the reflex of a man watching consequences arrive. On another, it gives you a brutal measure of where his mind first went. Family, self, fallout.

Then there’s the line that matters more, the one that cuts past any courtroom performance or carefully arranged mitigation. In the footage, he acknowledges he has ruined so many lives. For once, he was right. Not in the self-pitying sense, not in the “feel sorry for me” sense, just the plain arithmetic of harm. The victims ranged from a baby in a pram to an elderly woman, and the injuries were not only physical. People who survive events like this carry it into crossings, into car horns, into crowded streets, into sleep. That becomes part of the price.

I’ve seen some say, “thank God no one was killed”, and I understand why that line appears first. It’s a human relief. It’s also a reminder of how close the city came to something even darker, and how narrow the gap can be between a headline you can stomach and one you can’t.

Media myths and the mask that slipped

Early coverage leaned on familiar shapes. A family man. A decent bloke. A moment of madness. Hints and nudges toward trauma, toward PTSD, toward some shadow from military service. The kind of framing that invites the audience to lean back and think, tragic really, as if the story is mainly about the perpetrator and his troubled interior.

Then the facts came out in court, and the costume did not fit.

Doyle had previous convictions for violence, including a notorious incident involving biting off part of someone’s ear, which led to prison time. The military angle, the insinuation that service explained the behaviour, also collapsed under scrutiny. The prosecution's position was that there was no link between his military service and the crimes, and he had not been deployed.

That matters because it reveals what the story always was. Not a man haunted into a trance, not a victim of circumstances spiralling out of control. A man with a history of aggression, who, on a packed city street, chose rage. He did not drift into disaster; he pushed his way into it.

There is another reason this myth-making sticks in the throat. Liverpool supporters have spent decades being spoken about as a problem to be managed, a crowd to be suspected, an easy target for lazy narratives. So when you see any suggestion, however indirect, that fans brought this on themselves, that they attacked a car first and forced a frightened driver’s hand, you hear an old tune trying to start up again.

The court evidence described what happened in blunt terms. This was not fear dictating actions, it was temper. Even allowing that people struck the car at some point, the idea that this excuses accelerating into a closed street full of supporters fails on the basics. If you are scared, you stop. You do not drive through bodies. You do not keep going when you are hitting people, and you do not do it knowing children are in that mass.

The “family man” framing falls apart for another reason, too. Plenty of people have families. Plenty of people have rough days. Most do not respond by turning a vehicle into a weapon.

Justice, punishment, and the urge for vengeance

The comments after sentencing were a portrait of the modern public square. Grief. Fury. Confusion about what prison terms actually mean. Calls for never driving again. Arguments about whether 21 years is too light or too heavy, and whether other countries would pile on more time.

I’m not interested in treating a sentence like a football score, as if “more” automatically means “better”. I’m interested in whether the punishment reflects the intent, the scale, and the lasting damage.

This sentence is long by UK standards, and it reflects multiple serious offences. It also reflects the reality that this was not one victim, one injury, one reckless moment. This was a sweep of harm across dozens of people, including children, on a day the city had offered up as a safe, communal celebration.

Some wanted “prison justice”. I get the impulse, that raw desire to see pain answered with pain. It’s also the sort of talk that stains everything it touches. A society that hands out punishment has a duty to keep its head. The victims deserve dignity and support, not a blood sport carried out in their name.

Where I do agree with the angriest voices is on responsibility. Doyle’s remorse, described by his defence, does not reverse a degloving injury, does not wipe out nightmares, and does not restore a child’s sense of safety in crowds. Remorse can exist, and the consequences still stand like a wall.

And the so-called facade has gone now. The “family man” cushioning, the PTSD haze, the borrowed sympathy. What’s left is a clear picture. A man who lost his temper, drove into a crowd, and then tried to sell a story about fear that did not match the footage.

Lessons Liverpool must demand

There is one more uncomfortable truth here, and it sits alongside personal culpability, not in place of it.

Events of this scale need systems that anticipate the worst day, not only the best one. Hundreds of thousands of people in a city centre, closed roads, temporary measures, the slow churn of post-parade movement, transport bottlenecks, frustration everywhere. That is a combustible mix even before you add someone with poor impulse control and a steering wheel.

Questions about event management will keep coming, and rightly so. How did a vehicle get into that space? What checks failed? What barriers were missing? What protocols were assumed rather than enforced? How does the city plan routes, stewarding, dispersal, transport, so families can celebrate without being exposed to needless risk?

None of that dilutes Doyle’s guilt. It simply recognises a wider duty. Liverpool will celebrate again, it always does, and it should. The point is to make it harder for any individual, on any bad day, to reach a crowd with the means to do this sort of damage.

Because that’s the line I keep coming back to, the one he spoke without meaning to tell the truth. He said he’d ruined so many lives. He was right. The court has now put a number on what he did, 21 years and six months. The city will live with the rest, in quieter ways, for longer than that.