An Expert Review of Conor Bradley’s Injury Timeline

Why his workload history made this outcome increasingly likely

Some injuries are defined by force, others by timing, and some by severity. This one is defined by what it reveals about a career that has never quite been allowed to stabilise.

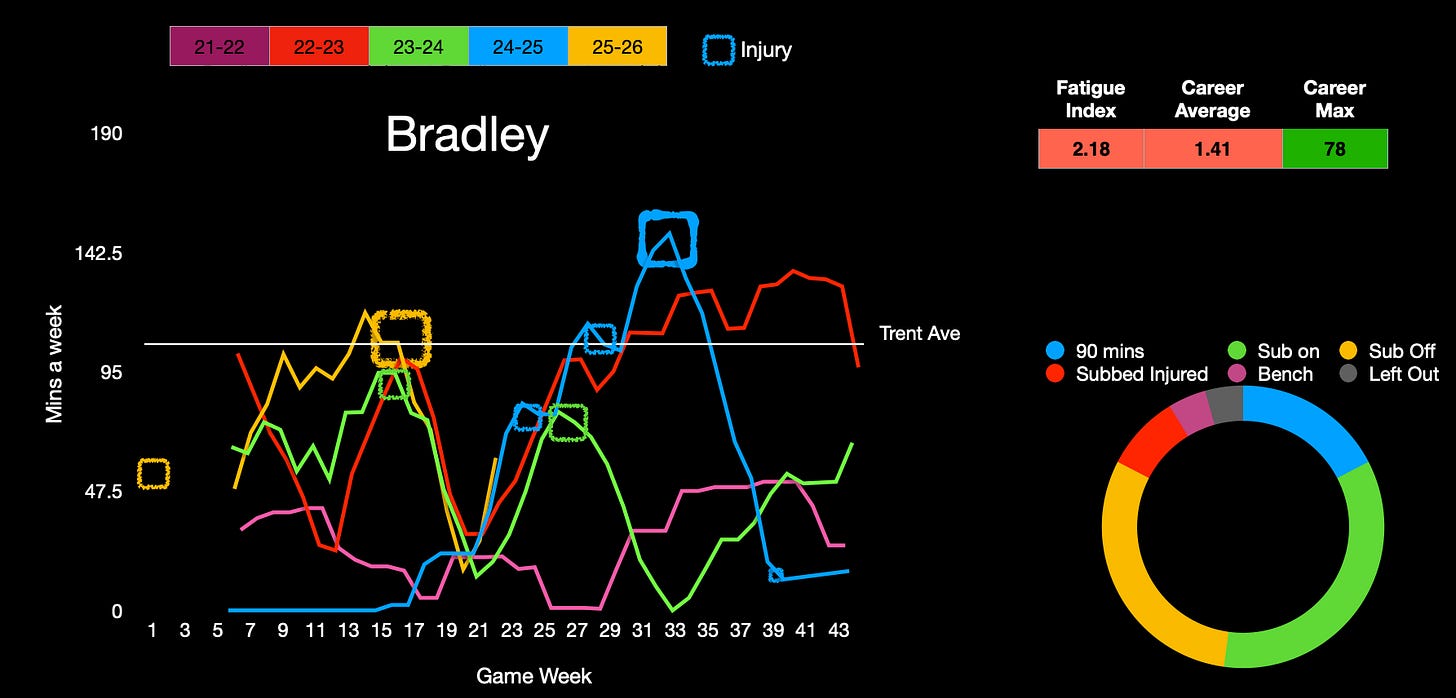

Conor Bradley was injured ninety six minutes into a high intensity away match at Arsenal. It was his fourth injury of the season, the second time he has been forced off mid-game, and the ninth injury of his senior career. Surgery is required, and a twelve month absence is a realistic expectation. That alone makes this injury significant. The deeper issue is how predictable this moment looks when viewed through the lens of his career to date.

Bradley’s return to action followed a pattern that has become familiar. Nineteen days earlier he had been withdrawn after fifty minutes against Tottenham. He returned with a thirty six minute substitute appearance against Wolves. He then started and played eighty minutes at home to Leeds on New Year’s Day, completed one hundred and two minutes away at Fulham on January fourth, and started again away at Arsenal. Across fourteen days, he accumulated approximately three hundred and fourteen competitive minutes.

For an established Premier League defender, that figure is not remarkable. For a player with Bradley’s exposure history, it matters a great deal. Across his entire career, he has only once completed more than two hundred and fifty minutes in a two week period without subsequently sustaining an injury, and that was two years ago. The only season in which he exceeded three thousand minutes came in the Championship. As a Premier League player, he has never passed roughly two thousand three hundred minutes in a campaign.

Adaptation does not occur in bursts. It is built through sustained exposure that becomes routine. Players adapt to the speed of the game, the density of training, the rhythm of recovery, and the emotional weight of expectation only when those demands are applied consistently enough to normalise them. Bradley’s career has rarely allowed that process to complete.

Chronologically, he is twenty two. Developmentally, he is younger. Each time momentum has built, something has intervened. Injuries have arrived frequently enough to disrupt continuity, but not always severely enough to force long periods of structured rebuilding. The result has been repeated resets. Tolerance rises briefly, is tested quickly, then collapses again.

This is what false starts look like in elite football. They are rarely dramatic. They do not announce themselves with catastrophic moments early in a career. They accumulate quietly through interrupted training blocks, disrupted rhythm, and repeated attempts to re-establish baseline capacity. The player is never fully unfit, but never truly robust either.

Players who transition cleanly into senior football usually do so through volume and repetition. They train every day. They play regularly. They travel, recover, repeat, and gradually learn what normal feels like at that level. Their tissues adapt. Their nervous systems adapt. Their psychology adapts. Bradley has rarely been afforded that runway.

The injury itself was not the result of a reckless challenge or an obvious collision. Arsenal launched a high ball over his right shoulder. Bradley turned and ran approximately forty metres under pressure from Gabriel Martinelli. As he attempted to clear with his right foot, he planted on his left. The plant foot slipped laterally on contact. He arrived slightly off balance, with a small hop on entry. The slip introduced shear forces through the knee, and the attempted clearance across his body created rotational torque. Compression from landing, shear from the slip, and rotation from the clearance combined in a way the joint could not tolerate.

This is a common mechanism for serious non ACL knee injuries in football. They often occur in moments that look routine, when multiple forces converge faster than the joint can dissipate them. They are not freak accidents, but neither are they simple overload injuries. They sit in the space where exposure, fatigue, surface interaction, and movement intent overlap.

Without going into specific structures, this injury involves both bone and ligament. It is not an isolated soft tissue issue and it is not something that resolves with rest alone. Surgical fixation is required. Decisions made in the operating theatre will influence joint alignment, stability, and long term tolerance to load. For a defender whose role depends on repeated accelerations, decelerations, lateral movements, and physical duels, this is a significant injury.

The rehabilitation ahead will be long. Early phases will prioritise protection and healing. Weight bearing will be progressed cautiously. Muscle loss is inevitable. Movement quality will take time to restore. Ligament involvement complicates return to performance even after return to play. Players often report that confidence lags behind clearance, and subconscious protection can persist long after objective markers appear satisfactory. This is where careers can stall if progression is rushed.

A fair question now exists. Has Bradley’s body ever fully adapted to Premier League football. Elite football is not defined solely by match minutes. Training is daily. Travel is constant. Recovery is compressed. Psychological load increases as expectation grows. Bradley is no longer a peripheral squad player. He has become a trusted option in major fixtures and the captain of his country. That change brings pride, but it also brings responsibility and additional load.

Adaptation requires continuity. Continuity requires availability. Bradley’s career has been short on both.

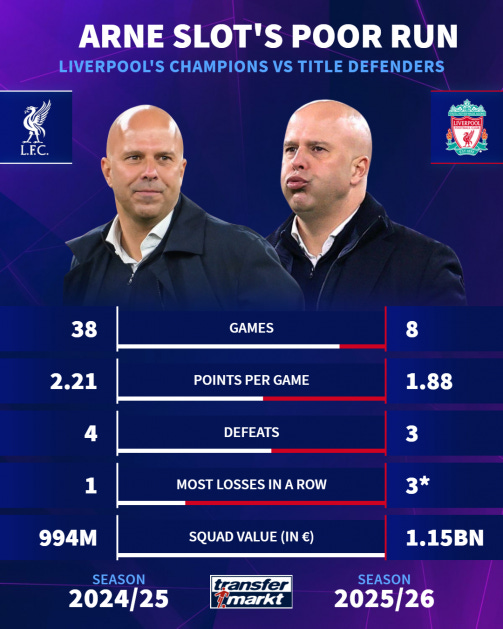

Football, however, does not operate in an idealised developmental model. It is a results first business. Selection decisions are made under pressure, often with incomplete information, and rarely with the luxury of long term thinking. Managers are judged week to week. Momentum matters. Form matters. League position matters. In that environment, what is optimal for development or injury risk reduction can drift away from what feels necessary in the moment.

At Liverpool, this season has carried additional weight. Following a difficult run of form in the autumn, the priority shifted firmly toward immediate results. Arne Slot inherited a squad under scrutiny and a title race that offered little margin for error. In those conditions, selection inevitably becomes conservative. Players who have contributed to positive outcomes are more likely to be trusted again, particularly in high leverage fixtures.

This is where psychology intersects with physiology. A positive result creates a desire to repeat the same solution. Continuity feels safe. Change feels risky. For a player returning from injury, that dynamic can accelerate exposure before a sufficient chronic load has been rebuilt. The player looks available, performs well in a limited window, and is then asked to do more because the team needs stability.

Modern football places enormous demands on the acute to chronic workload balance. Teams competing twice a week require players whose recent training and match history can support repeated high intensity outputs with limited recovery time. When chronic load is low due to interruption, acute load rises rapidly once minutes accumulate. That imbalance does not guarantee injury, but it increases vulnerability, particularly in positions that involve repeated sprinting, deceleration, and contact.

Overplaying rarely feels like overplaying in real time. It often feels like trust. It feels like momentum. It feels like responding to form. A player who helps the team win becomes harder to leave out, even if the underlying exposure profile suggests caution. By the time risk becomes visible, the exposure has already occurred.

In that sense, injuries like Bradley’s are rarely the result of a single decision. They emerge from a convergence of competitive pressure, psychological reinforcement, fixture congestion, and the simple reality that football prioritises the next result over the next twelve months.

This injury does not only affect Liverpool’s season. It almost certainly removes Bradley from international contention during a critical period. He is likely to miss the opportunity to captain Northern Ireland through World Cup playoff matches, and possibly through a World Cup cycle itself. Those opportunities do not pause. They pass.

For a young player, that loss carries weight that extends beyond club football. International leadership is not guaranteed. It is earned, but it is also fragile. Time away creates gaps that others fill.

Bradley has a reputation as a tough competitor. His background in Gaelic games shaped his work ethic and physical resilience. He covers ground willingly, competes honestly, and does not shy away from responsibility. Those traits are part of why he is trusted. They are also part of why he is vulnerable. Tough players are often asked for more before they are ready to give it.

He has also experienced significant life stress early in his career. Losing his father after breaking into Liverpool’s first team is not a footnote. Emotional load does not disappear simply because performance is required. It accumulates alongside physical stress, even if it is rarely discussed.

Resilience is not infinite. Toughness does not strengthen bone or ligament. Character does not replace adaptation.

This is a severe injury and a major challenge. There is no benefit in minimising that reality. For a player whose career has been shaped by interrupted momentum, the next year matters more than the next run of fixtures. Rehabilitation must prioritise robustness over speed. Availability has to follow adaptation, not precede it.

If Conor Bradley is to establish a stable Premier League career, he needs something he has rarely had so far. Sustained time without interruption. Time to rebuild chronic load properly. Time to adapt to the full physiological and psychological demands of elite football. Time without being rushed back into decisive moments because the context demands it.

Football celebrates breakthroughs. It is less patient with rebuilds. Bradley is not starting again; he is a Champion, but he is being forced into another pause at a moment when continuity mattered most. Whether this becomes another false start or the foundation for long-term stability will depend less on bravery and more on restraint.

This is not about toughness. It is about time.

And time has not yet been kind to him.

Very sad for a player who does not know how to take a backward step. Badly managed? Absolutely.

Excellent read Simon love UP especially when you get deep into S&C and sport science.