Liverpool and Loss: Football’s Role When the Unthinkable Happens

Heysel, Hillsborough, and now Jota - Football has always carried the pain

When Football Must Carry the Grief

There comes a time when everybody needs to move on. That movement is often painful, but there’s no other option.

The friendly against Preston North End at Deepdale will test quite a few of Liverpool’s staff as they attempt to come to terms with the death of Diogo Jota and his brother Andre. Yet playing, and watching football, has a restorative quality. Some of us have learnt that from bitter experience.

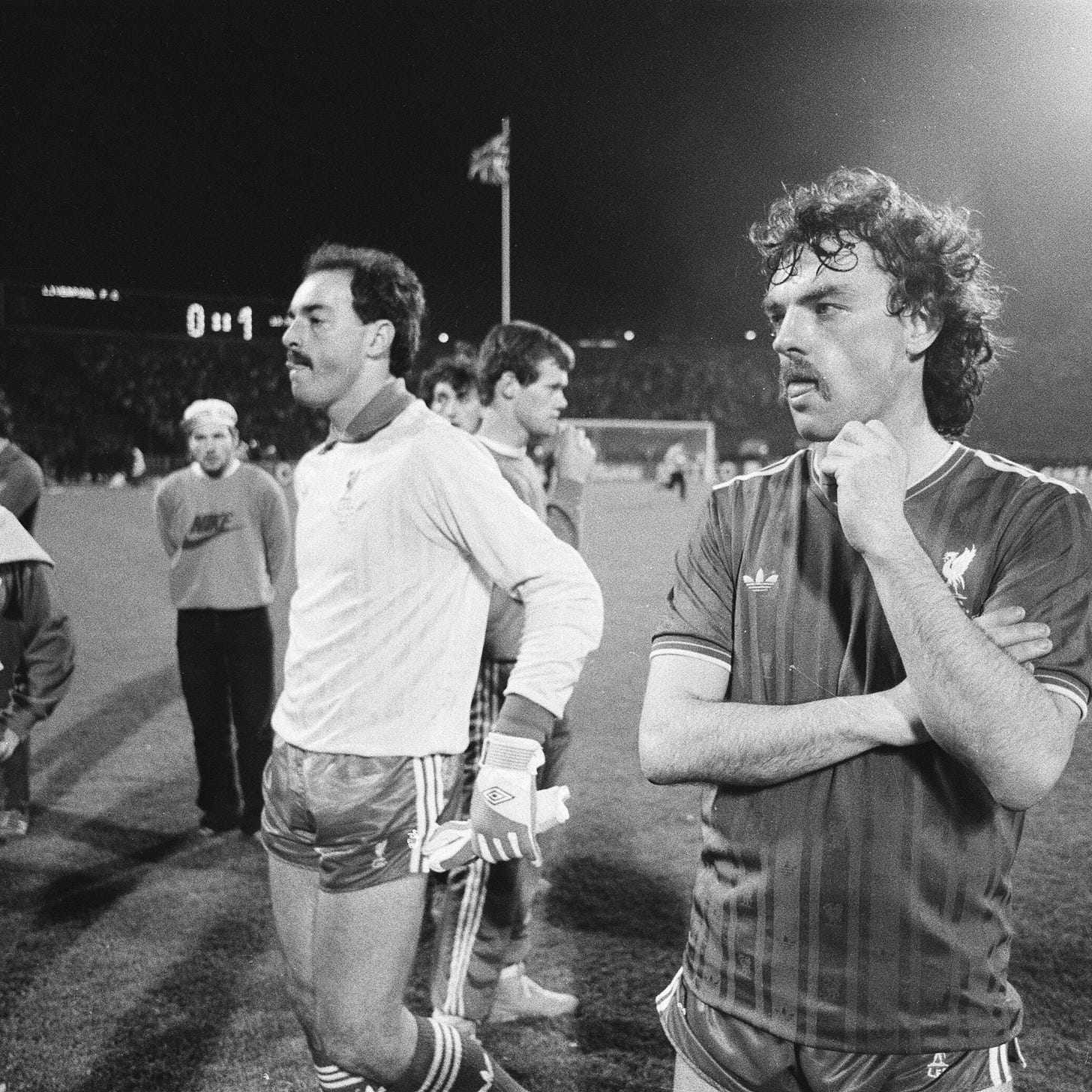

Ghosts of 1985: A Club in Denial

The summer of 1985 was a surreal experience. Circumstances were different because the mourning was not on Merseyside: it was being conducted in Italy and Brussels. The majority of us were trying to pretend that the 39 dead of Heysel were nothing to do with Liverpool fans.

That was delusional, of course. Condemnation filled newspapers and the airwaves. Lots of supporters said they would never attend another game after what happened at the European Cup final against Juventus. Bruce Grobbelaar says he thought about retiring from the game. It was obvious that things could never be the same after the mass fatalities in Belgium.

The disapproval on people’s faces told its own story wherever Liverpool fans went. The first pre-season match was at Burnley. The previous year’s campaign had started in Dortmund. We were in a new reality.

When we changed trains at Preston, passengers on the platform stared with contempt. “Why are they looking at us like that?” someone in our carriage asked.

“They’ve never seen mass murderers before,” one of the lads responded, sadly. He was making a point about how much of the world viewed us after the carnage of Heysel.

Over the course of the next 10 months, things changed. By the time Liverpool had completed the league and FA Cup double in May with a Wembley victory over Everton, our reputation had been restored. Global praise was heaped on the team and supporters, the game was on an upward trajectory and Grobbelaar was doing handstands to entertain the crowd. How the hell did football do that?

Because it moves on. Its motion is constant. Its uplifting characteristics elevate even the most damaged souls.

Hillsborough Changed Everything

An even more apt example came after Hillsborough in 1989. This time the horror was close to home. In the immediate aftermath of the unlawful killings at the FA Cup semi final against Nottingham Forest, it was hard to imagine how the game could continue as normal.

The players and staff spent two weeks attending funerals and wakes and there was little appetite to continue the season. Many of us argued completing the campaign would be an insult to the 95 who died on the Leppings Lane terrace (a number that’s grown to 97).

Yet anyone who attended the first game after Hillsborough will tell you it was one of the most emotional and cathartic experiences of their life. The result of the game at Parkhead is immaterial. Celtic had the brilliant idea of ignoring segregation and they sold tickets to groups of Liverpool fans in every section of the ground. The entire stadium was mixed. It gave real meaning to the term ‘friendly match.’

The climactic rendition of You’ll Never Walk Alone as the final whistle approached was beyond uplifting. Everyone seemed to be crying. It was the most impressive display of humanity and solidarity imaginable. Everything that’s good about football was expressed at that moment. Community, love and empathy came together. The part of us that could heal, began to heal.

There are wounds that can never be closed. The Silva family will always endure a gaping hole. For those of us with less personal ties to Diogo, the process of remembering the forward with a smile and not a tear is beginning. His mates in the squad will find that journey more difficult but they will get there eventually. Playing will help.

This is not a case of getting over it, it’s getting on with it. The time is right to think about football again.

New Faces, Strange Times

Spare a thought for the new arrivals at the club. Florian Wirtz, Jeremie Frimpong and Milos Kerkez were the names on everybody’s lips before they were upstaged in the worst possible way.

They are having to walk into a dressing room filled with grief. They will be sad, too, but Jota was not their friend and colleague.

Settling into a new club can be hard. The circumstances at Anfield make it even more difficult. Tragedy brings people together and outsiders can feel locked out.

Arne Slot and the club will be conscious of this and determined to make sure it does not happen. The sorrow of Jota’s loss affects everyone connected with Liverpool, even those who never played alongside him.

We will write less and speak less about Diogo Jota from now on. But make no mistake. He won’t be forgotten. No. Never, ever, forgotten.

The Hillsborough Law: A Test of Integrity

Remembering is in our DNA. Keir Starmer should bear that in mind.

In March, the draft version of the proposed 'Hillsborough Law' was shown to one of the barristers connected with the justice campaign. He was shocked and appalled that the Government's version of the bill was toothless and contained no legally enforceable duty of candour.

The KC was furious and let civil servants know. Starmer phoned him shortly after and was shocked to hear the reaction was so vehement. The Prime Minister squirmed out of a scheduled meeting with the families later in the week.

Ian Byrne, the MP for West Derby, is presenting the original bill to Parliament today, the version that was first laid before the Commons eight years ago. If the Government vote against it, this will be a massive betrayal by Starmer.

No, Liverpool does not forget. Nor does it forgive. And, Prime Minister, we are not going away.

I felt like that after Hillsborough.

👏👏👏👏👏